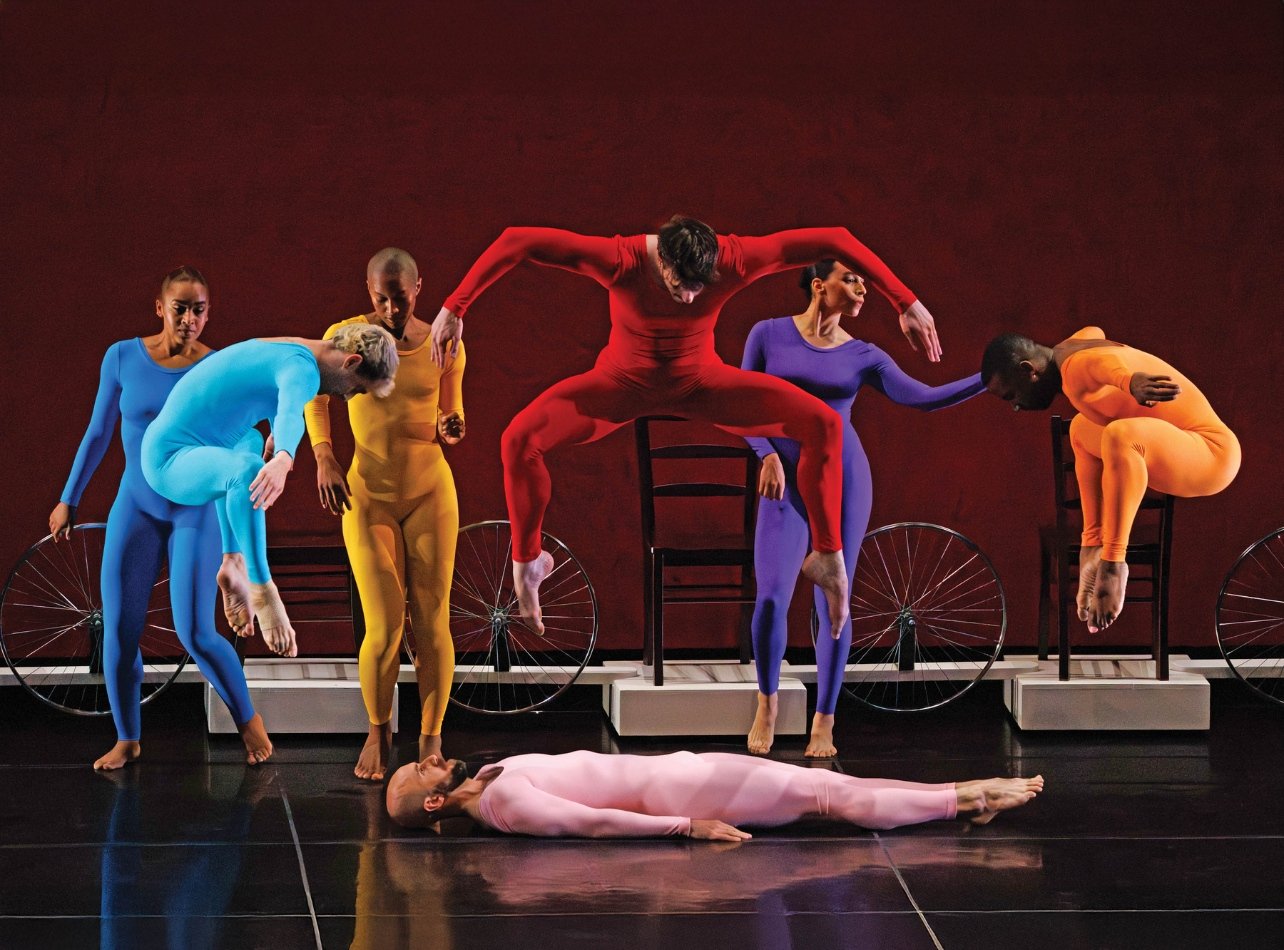

Opening night of Travelogue (1979), choreographed by Merce Cunningham; set design by Robert Rauschenberg. Photo by Ben McKeown, courtesy of The American Dance Festival.

A relentless boundary-breaker, Robert Rauschenberg spent his life collapsing the divisions between disciplines, between the material and immaterial, between art and life. One of the most poignant tributes to his radical imagination is “Dancing with Bob,” a yearlong performance program that revives two of his most enduring collaborations: Trisha Brown’s Set and Reset (1983) and Merce Cunningham’s rarely staged Travelogue (1977). Presented by the Trisha Brown Dance Company in collaboration with the Merce Cunningham Trust, the program premiered this June at the American Dance Festival in Durham, North Carolina—a fitting venue for an artist whose legacy was built on interdisciplinary entanglements.

“Dancing with Bob” doesn’t simply celebrate Rauschenberg’s work in dance—it restores it to the center of his practice. His earliest champions weren’t museum curators or postwar painters. MoMA didn’t acquire its first Rauschenberg until 1972, and only then as a gift from Philip Johnson. But from the 1950s onward, Rauschenberg was deeply enmeshed in the world of performance. It provided an early outlet and income. Alongside Cunningham and composer John Cage, he immersed himself in the collaborative life of the stage—not merely as a designer, but as a co-creator of fully realized environments. As Cunningham’s stage designer and technical director, he toured with the company, rigged lights, dressed sets, and helped invent a new vocabulary for what visual art could be.

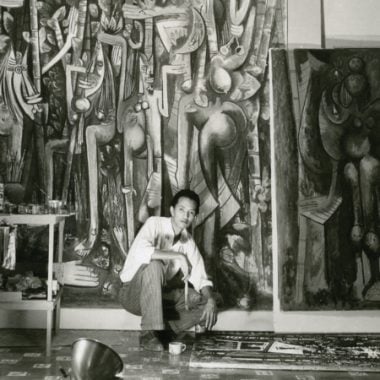

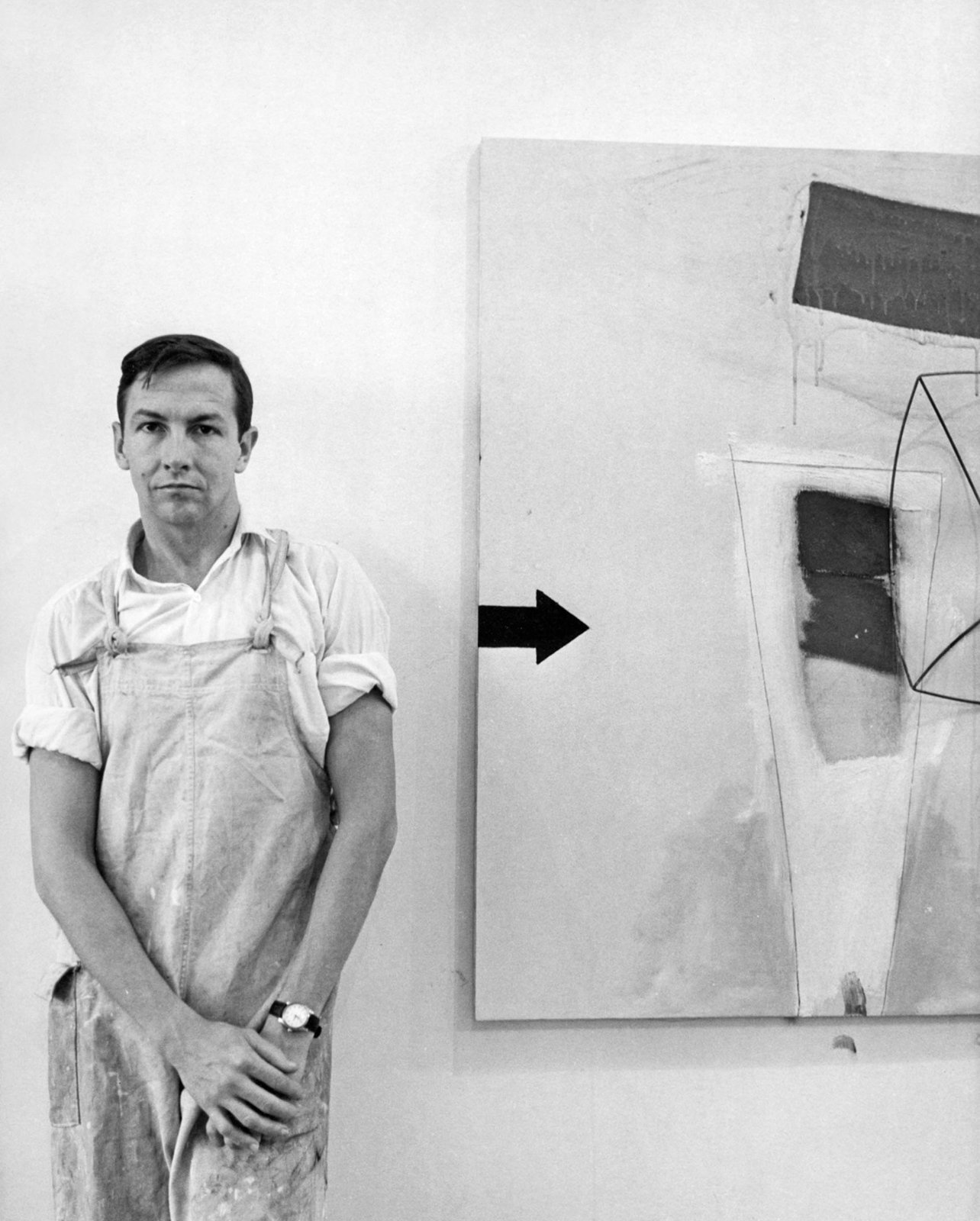

Robert Rauschenberg with his painting, Stripper, 1962, in his New York studio, 1962. Image courtesy of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archives, New York.

Together, they built on the legacy of legendary creative pairings—Balanchine and Picasso, Graham and Noguchi, Cocteau and Chanel—but pushed the form into new, more porous terrain. Or as Courtney J. Martin, executive director of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, puts it: “Few artists embraced collaboration as wholly and openly as Rauschenberg. From his early days, he consistently challenged conventional boundaries and reimagined what was possible across media. His work with Trisha Brown, Merce Cunningham, and Paul Taylor exemplifies the kind of interdisciplinary exchange that shaped his artistic vision.”

Rauschenberg’s success in the dance world stemmed from his gift for listening. He devoted hours to long, winding phone calls with creative partners, taking in their daily thoughts and emotional weather. But his attention didn’t stop there. He listened to the city itself—to its debris, its rhythms, its unguarded moments. The Texan-born artist believed that by tuning in to the unique forms and voices around him, he could respond in kind, producing objects that had never been seen in a theater or gallery: a parachute used as a backdrop, a chair worn like a costume. It was during this period, too, that he created the Combines, the hybrid sculptures that have become some of his most celebrated works.

A scene from Set and Reset (1983), choreographed by Trisha Brown; photo © Mark Hanauer.

In short, Rauschenberg’s instinct for assemblage grew out of his love of movement. And nowhere is this more palpable than in Travelogue, created in 1977 after a 13-year break in his relationship with Cunningham. The piece marked a reconciliation—and a shift. Gone was the austere minimalism of their early work; in its place came a sense of play and theatricality. Rauschenberg’s sets and costumes for Travelogue are uncanny and vaudevillian: tin cans, bicycle wheels, and sculptural props that render the dancers at once graceful and absurd. Staged at the American Dance Festival for the first time in nearly five decades, Travelogue feels less like a revival than an excavation. Its inclusion in the program points to the deeper goal of the centennial: to reexamine not just the canonical works, but the ones lost to time.

The second half of “Dancing with Bob” is devoted to Set and Reset, the result of a years-long collaboration with Brown. If Travelogue shows Rauschenberg leaning into the maximal, Set and Reset reveals his gift for lyrical atmosphere and translating choreographer intentions into environments. The piece unfolds in gauzy layers: transparent, newsprint-patterned costumes, floating scrims, and overlapping film projections that create a dense yet porous world. Brown’s choreography— fluid, loosely structured, deceptively improvised—plays with the flickering nature of visibility.

Travelogue (1979), choreographed by Merce Cunningham, set design by Rauschenberg. Photo by Ben McKeown, courtesy of the American Dance Festival.

Set and Reset is perhaps Brown’s most iconic work, and it stands as a testament to the alchemy between her compositional restraint and Rauschenberg’s layered sensibility. As with Cunningham, he wasn’t brought in to illustrate her vision—he helped shape its contours alongside her. That is perhaps the clearest throughline in all of Rauschenberg’s performance collaborations: a refusal to treat disciplines as separate or hierarchical. His contributions grew from the same urban, improvisational logic that drove his paintings and sculptures—chance, texture, juxtaposition—but with one crucial difference: onstage, the work lived.

“Dancing with Bob” returns us to the body—to the stage, where his ideas once leapt, spun, and sweated into being. It restores to view one of the most ephemeral, and most essential, aspects of Rauschenberg’s legacy. In that sense, it is not a memorial but a living archive—a reminder that collaboration remains one of the most radical acts of all.

The throughline in all of Rauschenberg’s performance collaborations is a refusal to treat disciplines as separate or hierarchical.

A Rauschenberg Road Trip

Across the country, cultural institutions are paying homage to the great American artist. Here, three standout exhibitions to consider:

Rauschenberg’s Mirage (Jammer), 1975. Image courtesy of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

“Robert Rauschenberg: Fabric Works of the 1970s” at The Menil Collection

Another under-recognized aspect of Rauschenberg’s practice was his relationship with fabric—a medium he treated with the same irreverent inventiveness as paint or print. “Robert Rauschenberg: Fabric Works of the 1970s” at the Menil Collection in Houston rights this historical oversight, gathering more than 45 sail-like assemblages that flutter, fold, and glow.

Costumes for Trisha Brown Dance Company’s Glacial Decoy, 1979, Walker Art Center. Photo by Ron Amstutz, courtesy of the Walker Art Center.

Trisha Brown and Robert Rauschenberg’s Glacial Decoy at the Walker Art Center

If you are looking for more Brown and Rauschenberg content, look no further than the Walker in Minneapolis, for a screening of Glacial Decoy (1979). It is a work that reflects on their foray into the medium of the moving image, which, thanks to technological innovations like the Sony Portapak, was becoming increasingly accessible to artists.

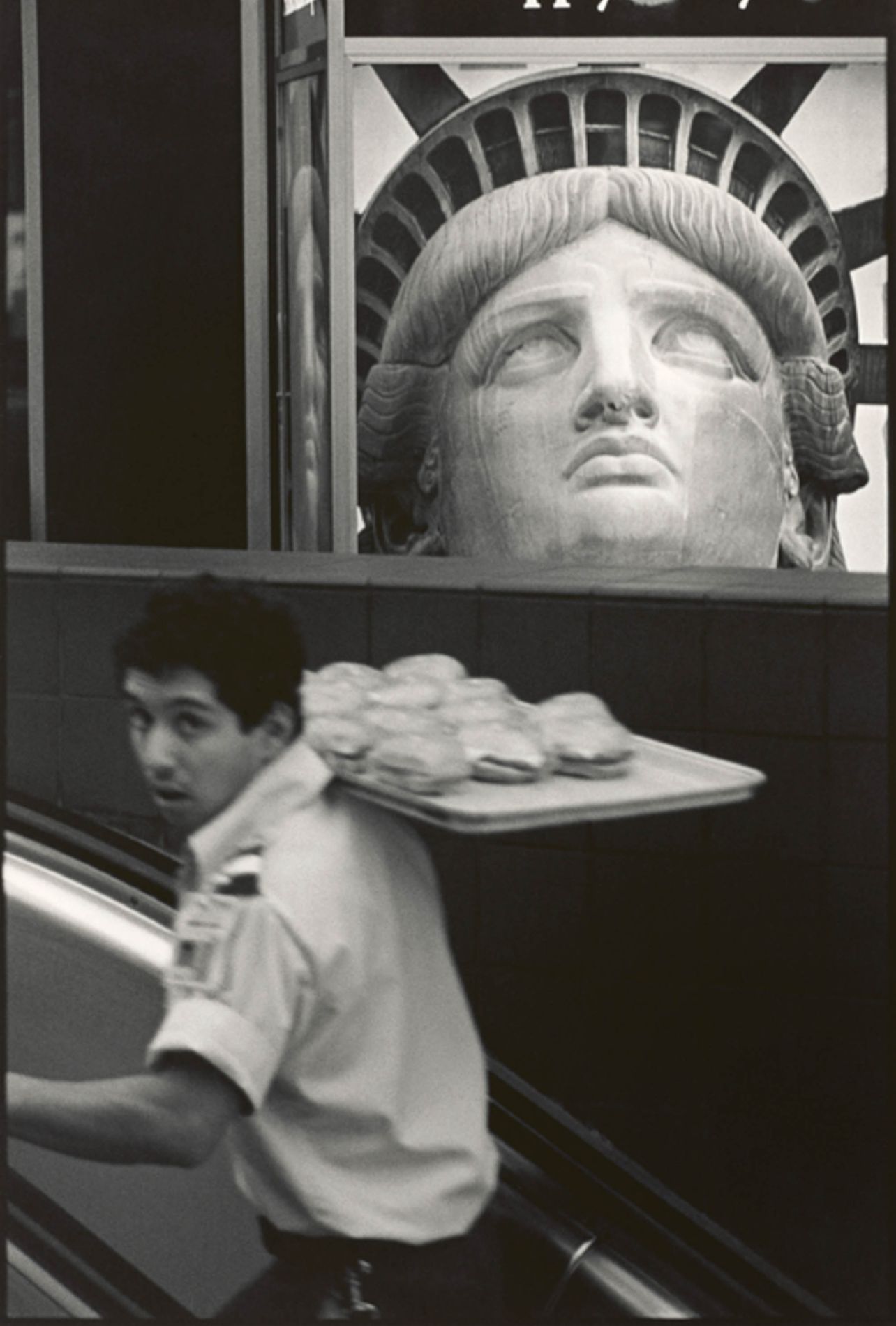

Rauschenberg’s New York City, 1983. Image courtesy of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

“Robert Rauschenberg’s New York: Pictures from the Real World” at the Museum of the City of New York

Long before smartphones and digital cameras, Rauschenberg roamed New York with his 35mm lens, photographing sidewalks, shadows, and fleeting encounters with equal wonder. This fall, the Museum of the City of New York celebrates this lesser-known side of his practice in “Robert Rauschenberg’s New York: Pictures from the Real World.” Featuring early portraits, street photography, and works that merge image with object, the show captures a city—and an artist—in constant motion.